Chapter Five: - The Forgotton

It was impossible to see inside.

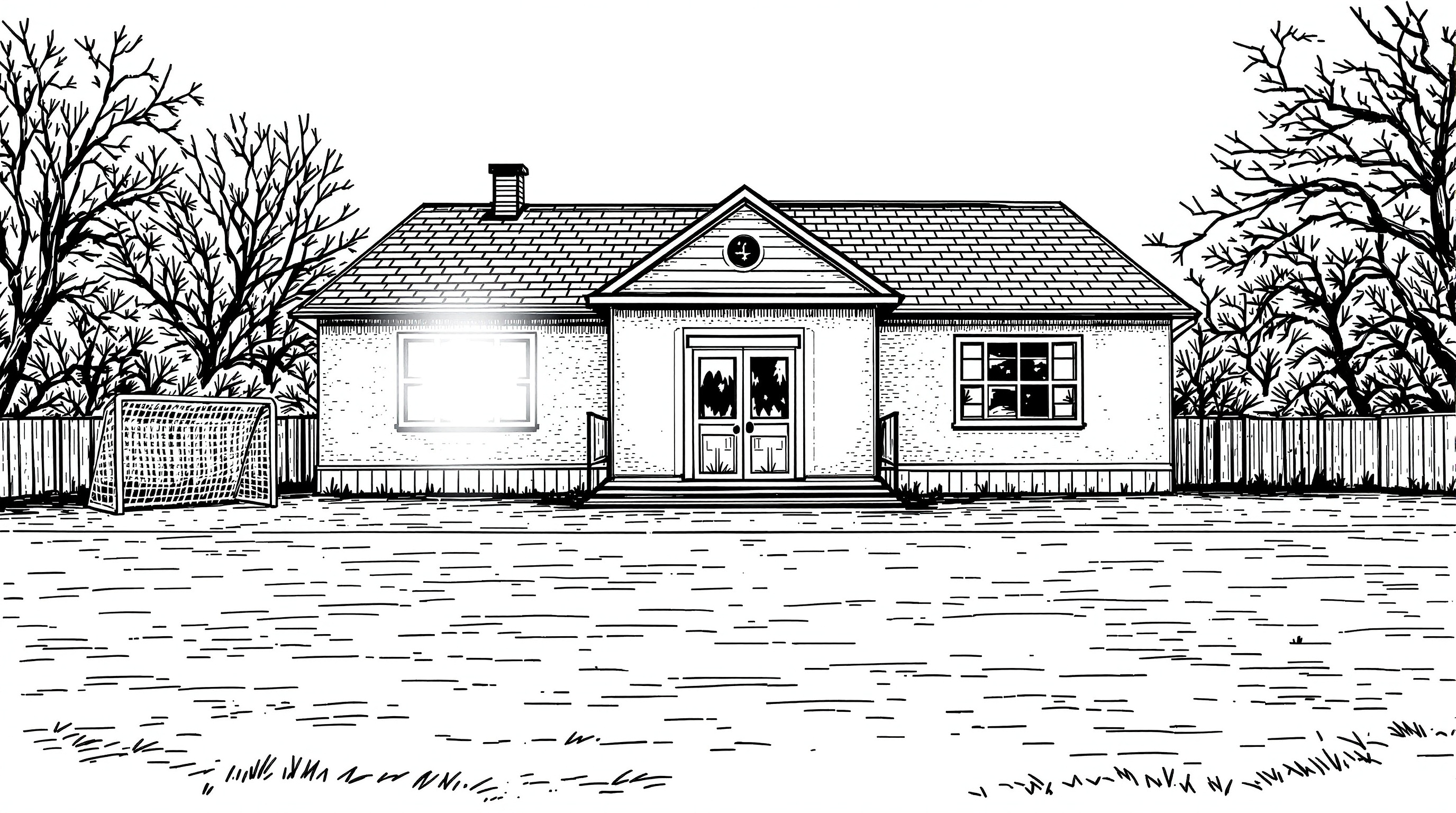

The pair ran into the playground area and stopped at the rear wall, catching their breath. Trisha looked at her watch: 2:34:17 p.m. Fifteen minutes till the end-of-day bell. Everything seemed normal. The sound of nearby cars, a bird singing somewhere.

“I want to see something,” said Jenkins. “Follow me.” He grabbed Trisha’s hand and walked to the other side of the playground where they stopped opposite the windows of the classroom they had been trapped in. Without getting close, they both stared. It was impossible to see inside, the whiteness was still there, covering the windows.

“What now?” said Jenkins. “They’re gonna want to know where those twenty-two kids have gone.”

“And what about Samuels?” said Trisha. “Was he part of this? I have a feeling he was — but unknowingly. He created a classroom full of misery for years, and when we went through the void—”

“And kids and years were changing,” added Jenkins.

“Yeah, somehow it’s all repeating. Something must be—feeding from that misery, sadness?”

“What, like food?” asked Jenkins.

“Maybe,” nodded Trisha. “You felt it, that atmosphere. You said you felt like hanging yourself.”

Jenkins smiled as Trisha pulled a large brush from her bag and started to run it through her hair. Typical woman, he thought. Brushing her hair at a time like this.

As she brushed they both noticed Mr Spencer walking towards them.

“What are you two doing here at this time?” he asked as he got closer. He was dressed in his usual muddy jeans, muddy boots, and had his winter coat open, a rake over his shoulder. He was followed by a few kids carrying gardening tools, packing away for the end-of-day bell.

“You lot take that equipment back; I’ll follow on in a minute,” said Mr Spencer to his followers.

He walked up to Trisha and Jenkins. “Well? Shouldn’t you two be in class?”

“We had Samuels,” said Jenkins. “We had to escape.” He knew Spencer wasn’t a fan of Samuels, and also that Spencer was a decent bloke — for a teacher. One of those who sometimes joined the kids in the fag pit at the back of the school.

“Samuels?” said Spencer. “Who’s that — one of those supply teachers?” He rolled his eyes in sympathy.

“What?” said Trisha. “No. Mr Samuels, maths?”

Mr Spencer looked at Trisha, puzzled. Strange that she was here with Jenkins — he didn’t realise the two were friends. “OK, what’s the punchline?” he asked with a smile.

“No punchline, sir. Jay Fowler, Ruth Muir?” said Jenkins.

Trisha watched Spencer’s face. It was blank, still smiling, not taking them seriously. “They’re in your class — you must know them?”

Spencer turned to walk away. “Maybe add a punchline to your gag, eh?” he suggested as he left them.

Trisha and Jenkins just stared at each other silently. Twenty-two kids gone — and a teacher.

“Are you sure we didn’t just imagine all that?” asked Trisha.

“How could we both imagine it?” replied Jenkins. “And look,” he said, pointing back at the classroom. The whiteness was still there, blocking any views through the windows. “Do you think it will stay there — or maybe come out?”

“I wonder if anyone else will be able to see it?” said Trisha. “Whatever that whiteness is, I reckon it's definitely feeding off Samuels’ cruelty.”

“Oh my God,” exclaimed Jenkins. “And he was due to retire this week.”

“Really? How do you know that?” asked Trisha.

“My old man’s on the school committee. Samuels turned sixty-five a few months ago and has been given retirement.”

Trisha nodded looking at the whiteness blocked windows across the playground. “So whatever that ‘whiteness’ is, it wanted to keep the misery and suffering going.”

“If you’re right,” said Jenkins.

“If I’m right,” she agreed.

The school bell rang, and quickly the yard filled with the hustle and bustle of doors opening and kids rushing out, home at last. “Look.” Trisha said and they watched as the whiteness faded, leaving the classroom windows clear. Whilst neither was prepared to go closer, they could vaguely see into the classroom from their distance. It seemed… normal.

They stayed in the playground watching as their peers poured out. Hoping against hope that the kids who had disappeared would all come walking out, none did. Jenkins approached a couple of his mates and asked about one of the missing kids. They looked at him blankly, having no idea who he was talking about.

“Come on, I’ll walk you home,” said Jenkins.

“What about tomorrow?” said Trisha. “No way I’m going back into that classroom.”

“Likewise,” agreed Jenkins. “Screw tomorrow — I’m bunking off. Last day of term anyway.”

“I’ve never bunked before,” said Trisha, considering the idea. The thought of coming back filling her with dread.

“Meet me at the café at 8:45 sharp and I’ll show you how.” Jenkins smiled as the pair walked home.

The only ones who knew that twenty-two children and a schoolteacher had been erased from time.

Had they ever existed?