Chapter One: - Just Another Day

On a cold, wet day, towards the end of lunchtime, a secondary school somewhere in England, 1984, was bustling with children milling around the corridors, avoiding the rain and instead chatting to friends or catching up on homework that should have been done the night before. Very few of them wanted to be there.

In the girls’ cloakroom sat Trisha with her best friend Cathy; they were flicking through the latest Smash Hits pop magazine, Duran Duran were still flavour of the month, and the pair were drooling over new pictures of Simon Le Bon and John Taylor.

“I bet John Taylor never uses any algebra to play the guitar,” Trisha moaned, feeling down at the thought of her upcoming maths lesson.

They had ten minutes left of freedom until the bell would ring and send them both separate ways: Cathy to Geography, Trisha to maths. It was the worst lesson of the week, a gruelling double session with old man Samuels — ‘Stinky Sam’ as he was commonly called behind his back.

‘Stinky Sam’ smelt of cigarettes and old age; the dourest teacher in the school and certainly the nastiest. Samuels delighted in teaching algebra while giving the least instruction on how to solve them. He would hand out textbooks and order the class to work from page ‘X’ onwards. His lessons were slow, tortuous, seconds passing by without end. Each Samuels class felt triple the length of a regular class. ‘Hell’ was how Trisha would describe it, she’d been saddled with him for the last four years.

For the majority of her classes, she did well. She disliked being forced to go to school, but as she had to attend by law, she tried to make the best of it when she had teachers who were willing to teach.

Tall for her age, with long fair hair and a friendly, open face, Trisha was maturing into an attractive young lady. With Cathy she flicked through the magazine, chatting away, Trisha’s mood turning darker as the ringing of the school bell became inevitable.

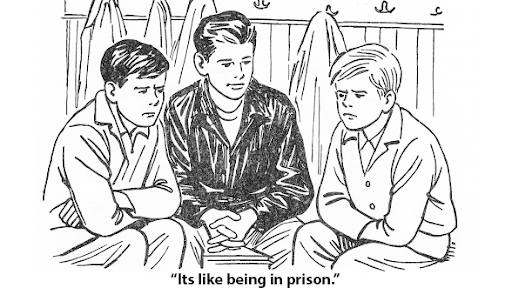

Across the corridor, the boys’ cloakroom buzzed with activity, and in a corner sat Jenkins and his mates Benny and Alan. All three of them equally despised the school system, all full of resentment. “Forced prison, isn’t it,” Jenkins often said.

“You joining me in detention today mate?” Alan asked Jenkins. Jenkins, around five foot ten and still growing, had a mop of black hair and a generally cheeky smile. He was slim and wiry, the kind of lad who looked like trouble even when he wasn’t trying.

“Nope,” laughed Jenkins. “I’ve got Stinky Sam, that’s enough suffering for one day.”

“Old man Samuels,” said Benny. “Bloody awful. Glad I dodged him this year!”

“Yeah, I can’t stand him,” answered Jenkins. “And it’s a ninety-minute class. Somebody kill me.” He stood and mimed stabbing himself in the chest.

“Only another year and a bit to go, mate,” said Alan. “Then we escape. Freedom.”

“Yeah,” said Jenkins, sitting back down, “if I survive that long. You coming down the yard after school?”

“Yeah, well, after detention,” said Alan.

Jenkins’ father ran a scrap metal yard, dismantling old cars and selling parts — sometimes restoring them. Last summer holidays, Jenkins had helped on a restoration project, showing the beginnings of real mechanical talent and he’d asked to work full-time and quit school, but while Dad was open to it, Mum insisted on education.

She always won.

To Jenkins’ mind, he learnt nothing in this dump, especially from a teacher like Stinky Sam. He despised that man.

“Did you see Cathy earlier?” Alan asked his mates in a quiet voice.

“Yeah,” said Benny. “Got a thing for her, have you?”

“Shut up,” responded Alan, giving Benny a light punch on the arm.

“Well, to be fair, she ain’t bad,” said Jenkins, standing and fidgeting. “She’s done some growing in all the right places, know what I mean, boys?” he added with a wink.

“I was thinking of asking her to the school disco,” said Alan. “You think she’ll say yes?”

“Unlikely with your ugly mug,” laughed Benny, quickly jumping out of Alan’s reach.

The dreaded school bell rang and the trio gritted their teeth and sauntered from the cloakroom, bidding fond farewells to each other — all heading to different classes. The school had long ago learned to keep them apart, all as bad as each other, with Jenkins generally leading the pack.

As the bell rang, Mr ‘Stinky Sam’ Samuels was in the staff room and lit up his fifth cigarette of the lunch hour. Looking around as his colleagues vacated the room, he inwardly smirked at Mrs Peterson as she awkwardly clutched a pile of exercise books she had spent her lunch break marking and tried to get the staff room door open without any free hands. You’ll learn not to bother, he thought, not offering to help. She was still of the belief the kids were here to be taught. Samuels was of the belief kids were here to be punished.

And there was Mr Spencer, the gardening teacher, carrying a trowel and a rake. All the young girls seemed to fawn over his boyish good looks. The school’s pin-up teacher, with his thin frame and smiling face. Always enthusiastic and upbeat, he irritated Samuels. Why has he brought gardening tools into the staff room?

Plumes of stale cigarette smoke filled the room, escaping into the corridors each time the door was opened and closed. Two days to go until retirement, forced retirement, and then what, wondered Samuels. Spend all my time at home with Enid? No thanks, that marriage has been dead in the water for years.

What’s it all for? he wondered for the umpteenth time. Thirty-nine years serving this school, the end result being one paid-off mortgage and a lousy marriage.

Mr Samuels was medium height, sixty-five, and with a sallow face that looked miserable whether he was angry or smiling, the latter being very rare. It was as if his mindset had shaped the way he looked. Wearing a standard dark suit and polished shoes, what little hair remained was silver grey and slicked back with Brylcreem. His look was finished off with a pair of basic black spectacles sitting upon his beaky nose.

He finished off his cigarette, stubbing it out in the overflowing ashtray — not his job to empty, Where on earth is that cleaner woman? He stood up and left the staff room: ninety minutes of algebra with class 4G. Wonderful.

The school corridor was empty now, three minutes since the bell had rung. All the children were in their classes. Tucking his hands in his pockets, he took a slow walk to the classroom that had been his for thirty-nine years, and he liked it that way.

Over the years he’d given the room his personal touch: posters of algebraic and trigonometric formulas alongside pictures of the Queen and another of Winston Churchill.

At the back of the room, wall mounted, stood a glass display case. Inside, a stuffed badger crouched on a patch of fake grass, its fur long since dulled to a dusty grey. Its lips were pulled back in a permanent snarl, yellowed teeth bared as if frozen mid-attack.

The glass reflected the overhead strip lighting, giving the creature’s eyes a faint glint that made it look alive. Most of the kids hated sitting near it. For that reason he kept it.

Samuels turned the last section of the corridor and, no surprise, Jenkins was just heading into the classroom. Late. He hated that kid. Cocky, confident, full head of hair, always messing about, giving lip. They’d had several run-ins over the years, and Samuels had twice put in cane requests to the headmaster. The headmaster had overruled the first one and Jenkins’ parents had disallowed the second.

This had increased Samuels’ resentment of the child, alongside the fact that Jenkins had a brain, a good brain, and with that, confidence to boot. He’d probably go far and Samuels hated to think of any of his pupils doing well in life. He sighed — only a ninety-minute class, then home. He preferred the mornings with the whole day ahead of him.

Trisha looked around as Jenkins slouched into the classroom looking as depressed as she felt. Last one in, typical of him. Mind you, Stinky Sam hadn’t turned up yet. She watched Jenkins walk across to his usual desk, acknowledging a couple of kids in the class as he went. The desks were unallocated but they generally all sat in the same one each week. But today Richard Davis was sitting at Jenkins’ window desk.

She hoped this wouldn’t lead to a fight. Samuels was the sort of teacher who would hold a whole class back after the bell, just because of one kid causing trouble. She watched as Jenkins leant on ‘his’ desk and growled at Richard Davis, “That’s my desk, Davis. Move.”

Fortunately, Samuels came in at that point. God, you’re awful, thought Trisha, looking at his miserable face, the smell of stale cigarettes already wafting into the room. The tick of the clock above Samuels’ desk was annoying as well; it seemed to delight in going slowly, making each second last. Tick. Tock. Continuous.

Jenkins noticed Samuels’ entry and flicked Richard Davis’ textbook onto the floor as he walked to the only empty desk left at the front of the room, next to Trisha. He sat down, gave her a brief stare and, surprisingly, offered no quip, instead making himself as comfortable as he could on the hard wooden chair.

He moaned within, he’d sort that bloody Davis out later. The only way to survive this lesson was to gaze out of the window, which overlooked the empty school playground, and count the seconds until freedom. He hated this desk; it was only two desks away from Samuels who, as always stank of fags.

Looking around the room, Jenkins knew all the kids: all okay, none mates really, just fellow sufferers of the school system. Lee Edwards — back row, far corner — a far better position. Lee was okay, a bit boring, but easy to make laugh. Jenkins ripped off a section from his textbook and started scribbling a note. 'Oi Lee'.

“Carry on from last week. Page 535, section J,” Mr Samuels barked his orders as he marched into the classroom firmly shutting the door behind him. “Copy all the examples and work out the solutions.” He sat down at his desk and pulled out the class register. Looking around the room he counted the heads — twenty-four. Good, that matched what it should be, and without calling the register he ticked off all the names. He hated having to speak to them.

Trisha made a start, slowly copying the exercises over to her textbook. It’s flippin’ pointless. She glanced at her watch: 1:37:00 p.m. Only two minutes had passed since Samuels had barked his orders. Awful man. Her wrist was already beginning to ache as she wrote.

If 5x + 7 = 27, solve for x.

It meant nothing to her, and nothing in the exercise book was designed to explain it. Trisha recalled a time in one of her first maths lessons with Samuels during her first year. He had reduced her to tears in front of the class, calling her thick and stupid because she was unable to understand the maths being taught and had asked for help. She never asked again.

Glancing around the room, all of the other kids were likewise copying the text and she saw a few others already supporting their wrists, trying to ease the ache — only a few minutes into the task. But better a wrist-ache than a detention from Samuels, she figured.

Jenkins, next to her, was slouched over his desk scribbling a note. She wondered how he was going to pass it under Samuels’ gaze. He didn’t seem bothered about copying the maths formulas. Trisha had always found him to be an annoying, mouthy kid but lately he’d quietened down, and she almost admired his silent refusal to do this pointless exercise.

Trisha let her depression develop and carried on writing, gazing out of the window often, constantly looking at her watch. 1:38:03 p.m. so bored.

Tick

Oi Lee, quick note to say nothing of any interest here!! J

Jenkins scrunched the note up and thought, how to make delivery. With Stinky Sam less than two metres away, discretion was a must.

He looked over to Lee’s desk. Lee wasn’t there.